LOS EXPERIMENTOS QUE PERMITIERON A MENDEL DESCUBRIR LAS LEYES SOBRE LA HERENCIA GENÉTICA

Gregor Mendel

INTRODUCCIÓN

En este

último punto del blog vamos a estudiar y analizar el perfil personal y profesional

de Gregor

Mendel (1822-1884), su entorno, su personalidad, su biografía y todo cuanto contribuyó a diseñar

su personalidad religiosa y sus experimentos en genética hereditaria.

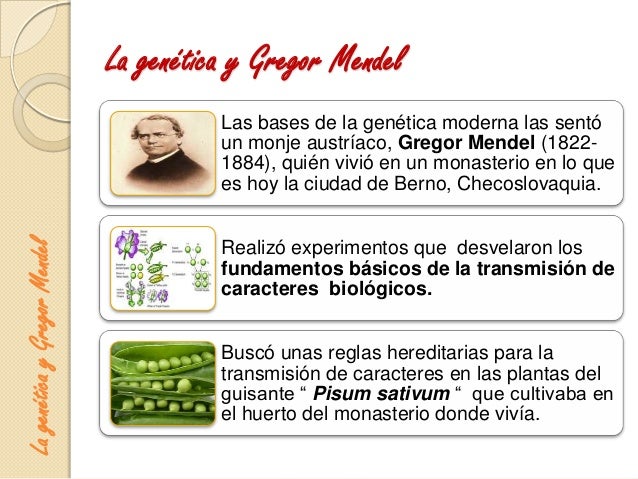

Con la

presentación del siguiente documento gráfico podemos aproximarnos a

la comprensión del trabajo realizado por Gregor Mendel y sus implicaciones en

la construcción de la genética como disciplina científica.

a) Historical context

Gregor Mendel was an Austrian monk who

discovered the basic principles of heredity through experiments in his garden.

Mendel's observations became the foundation of modern genetics and the study of

heredity, and he is widely considered a pioneer in the field of genetics.

Casa natal de Juan Gregorio Mendel

Early Life

Following his graduation, Mendel enrolled in a

two-year program at the Philosophical Institute of the University of Olmütz.

There, he again distinguished himself academically, particularly in the

subjects of physics and math, and tutored in his spare time to make ends meet.

Despite suffering from deep bouts of depression that, more than once, caused

him to temporarily abandon his studies, Mendel graduated from the program in

1843.

That same year, against the wishes of his

father, who expected him to take over the family farm, Mendel began studying to

be a monk: He joined the Augustinian order at the St. Thomas Monastery in Brno,

and was given the name Gregor. At that time, the monastery was a cultural

center for the region, and Mendel was immediately exposed to the research and

teaching of its members, and also gained access to the monastery’s extensive

library and experimental facilities.

Monasterio de Agustinos de

Brno

In 1849, when his work in the community in Brno

exhausted him to the point of illness, Mendel was sent to fill a temporary

teaching position in Znaim. However, he failed a teaching-certification exam

the following year, and in 1851, he was sent to the University of Vienna, at

the monastery’s expense, to continue his studies in the sciences. While there, Mendel

studied mathematics and physics under Christian Doppler, after whom the Doppler

effect of wave frequency is named; he studied botany under Franz Unger, who had

begun using a microscope in his studies, and who was a proponent of a

pre-Darwinian version of evolutionary theory.

In 1853, upon completing his studies at the

University of Vienna, Mendel returned to the monastery in Brno and was given a

teaching position at a secondary school, where he would stay for more than a

decade. It was during this time that he began the experiments for which he is

best known.

b) Descriptions

of the experiments step by step, using images to illustrate the main ideas.

A continuación se pone este original documento donde unos

alumnos resumen de forma animada los cruces que Mendel llevó a cabo en sus

experimentos para posteriormente convertir estos experimentos en sus leyes de

la genética.

This video offers a description of the

monohybrid (single trait) controlled cross developed by Gregor Mendel and used

by geneticists ever since. It is the most basic type of cross and often the

first learned when studying genetics at any level.

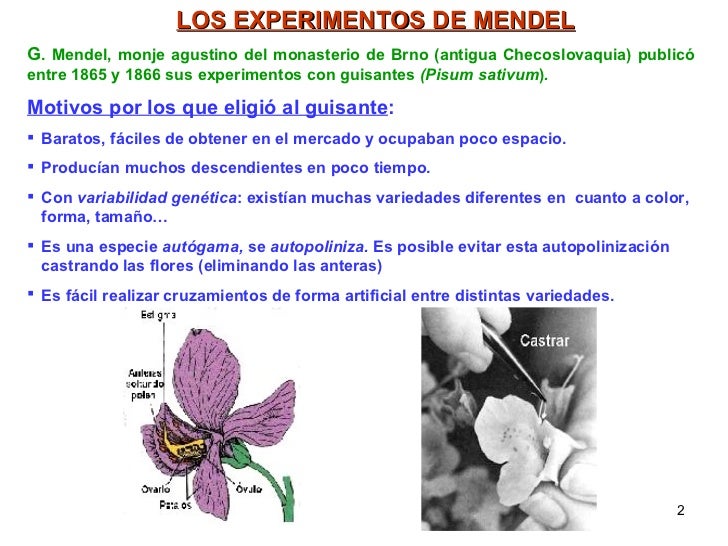

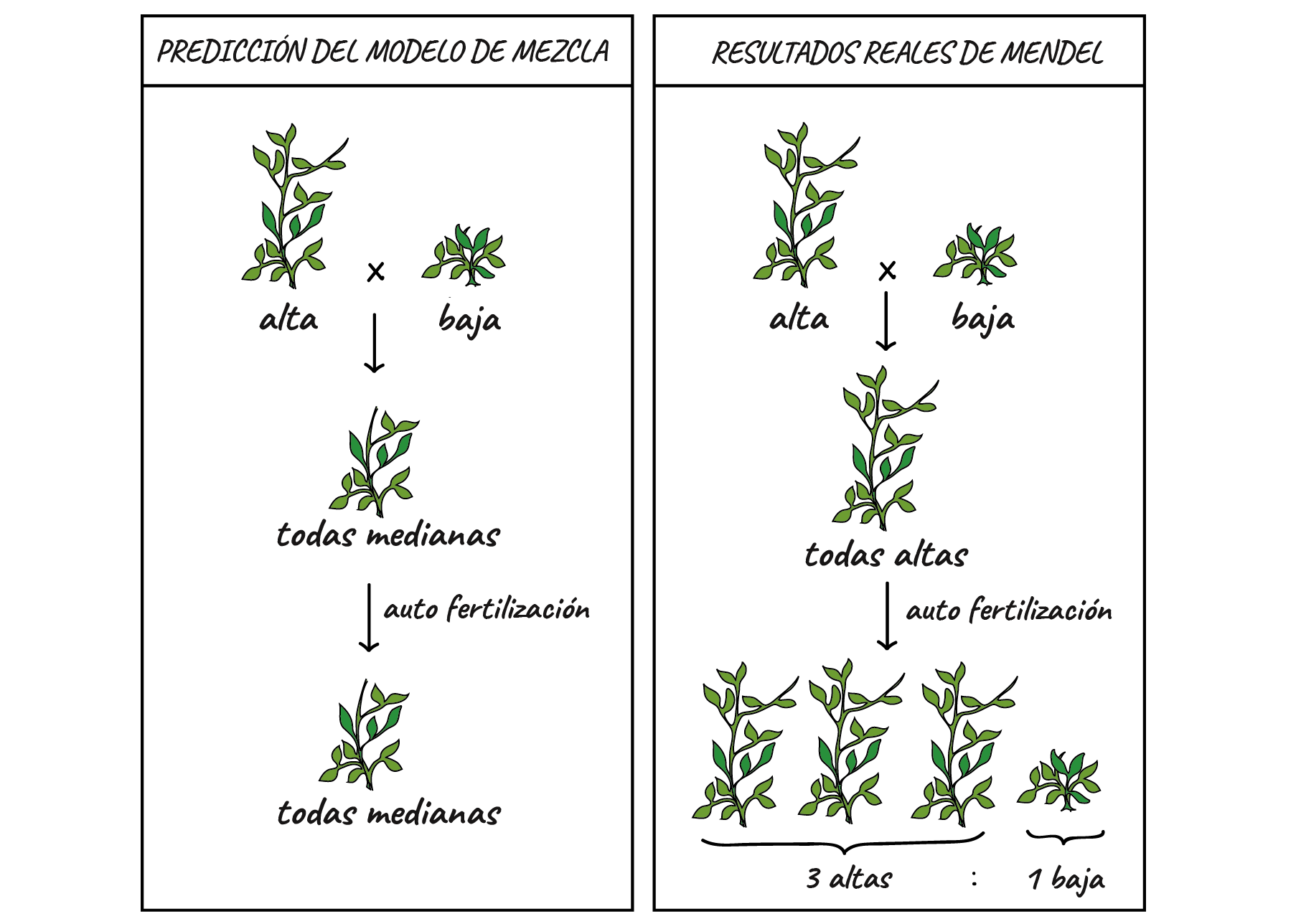

Around 1854, Mendel began to research

the transmission of hereditary traits in plant hybrids. At the time of Mendel’s

studies, it was a generally accepted fact that the hereditary traits of the

offspring of any species were merely the diluted blending of whatever traits

were present in the “parents.” It was also commonly accepted that, over

generations, a hybrid would revert to its original form, the implication of

which suggested that a hybrid could not create new forms. However, the results

of such studies were often skewed by the relatively short period of time during

which the experiments were conducted, whereas Mendel’s research continued over

as many as eight years (between 1856 and 1863), and involved tens of thousands

of individual plants.

Mendel chose to use peas for his

experiments due to their many distinct varieties, and because offspring could

be quickly and easily produced. He cross-fertilized pea plants that had clearly

opposite characteristics—tall with short, smooth with wrinkled, those

containing green seeds with those containing yellow seeds, etc.—and, after

analyzing his results, reached two of his most important conclusions: the Law

of Segregation, which established that there are dominant and recessive traits

passed on randomly from parents to offspring (and provided an alternative to

blending inheritance, the dominant theory of the time), and the Law of

Independent Assortment, which established that traits were passed on independently

of other traits from parent to offspring. He also proposed that this heredity

followed basic statistical laws. Though Mendel’s experiments had been conducted

with pea plants, he put forth the theory that all living things had such

traits.

Condiciones experimentales de Mendel

Una vez que Mendel había establecido líneas de guisantes

genéticamente puras con diferentes rasgos para una o más características de

interés (como altura alta vs. baja), comenzó a investigar cómo se heredaban los

rasgos realizando una serie de cruzamientos.

Primero, cruzó un

progenitor genéticamente puro con otro. Las plantas usadas en este cruzamiento

inicial son llamadas generación P o

generación parental.

Mendel recolectó las

semillas del cruzamiento de la generación P y las cultivó. Estos descendientes

fueron llamados generación F1,

abreviatura para primera generación filial. (Filius significa "hijo" en latín, ¡así que este nombre es

un poco menos raro de lo que parece!)

Los experimentos de Mendel se

extendieron más allá de la generación F2, a las generaciones F3, F4 y

posteriores, pero su modelo de la herencia se basó principalmente en las

primeras tres generaciones (P, F1 y F2).

c) Diagramas para resumir las ideas

principales

Primera Ley De Mendel

La primera ley de Mendel, también llamada Ley de

la uniformidad de los híbridos de la primera generación, o simplemente Ley de la Uniformidad.

Segunda Ley De Mendel

La segunda ley de Mendel, también conocida como

la Ley de la Segregación, Ley de la

Separación Equitativa, o hasta Ley de Disyunción de los Alelos.

Tercera Ley De Mendel

La tercera ley de Mendel, también llamada Ley de la Herencia Independiente.

d) Preguntas relacionadas con las

ideas anteriores

¿En

qué consistieron los experimentos de Mendel?

Los

experimentos de Mendel sobre la herencia se realizaron con guisantes. Mendel

eligió está planta porque se reproduce con rapidez, permitiendo obtener varias

generaciones en un poco tiempo. Además, tiene rasgos que solo admiten dos

formas (los guisantes son lisos o rugosos, verdes o amarillos…) y son capaces

tanto de auto-polinizarse como de fertilizarse de forma cruzada.

En

sus experimentos, Mendel estudió siete características de la planta de

guisante: color de la semilla, forma de la semilla, posición de la flor, color

de la flor, forma de la vaina, color de la vaina y longitud del tallo.

Por

ejemplo, en una de sus pruebas Mendel cruzó dos variedades de guisantes: una

con flores purpuras y otra con flores blancas.

Esta era la generación P o parental, y su descendencia fue la F1 (primera

generación filial). La generación F1 luego se reprodujo por autopolinización,

Dando lugar a la generación F2.

El

resultado de la prueba fue bastante clarificador. Si en la generación parental

había el mismo número de guisantes con flores blancas que con flores purpuras,

en la F1 solo aparecieron flores purpura. Sin embargo en la generación F2

reaparecieron los guisantes con flores blancas, que representaron

aproximadamente ¼ de la descendencia.

¿Qué

concluyó Mendel con sus experimentos?

A

la vista de los resultados Mendel dedujo que el color purpura en la flor del

guisante era un rasgo dominante (A) y la flor blanca un rasgo recesivo (a).

Mendel observó el mismo patrón de herencia en otros seis personajes, cada uno

representado por dos rasgos diferentes. A partir de ahí llegó a las siguientes

conclusiones:

● Los

organismos tienen factores discretos que determinan sus características (estos

"factores" ahora se reconocen como genes)

●

Además,

los organismos poseen dos versiones de cada factor (estas 'versiones' ahora se

conocen como alelos)

● Cada

gameto contiene solo una versión de cada factor (ahora se sabe que las células

sexuales son haploides, es decir, solo tienen n cromosomas y no 2n, como el

resto de células del organismo)

●

Los

padres contribuyen igualmente a la herencia de la descendencia como resultado

de la fusión entre el óvulo y los espermatozoides seleccionados al azar.

●

Para

cada factor, una versión es dominante sobre otra y se expresará completamente

si está presente.

Later Life and Legacy

In 1868, Mendel was elected abbot of the

school where he had been teaching for the previous 14 years, and both his

resulting administrative duties and his gradually failing eyesight kept him

from continuing any extensive scientific work. He traveled little during this

time, and was further isolated from his contemporaries as the result of his

public opposition to an 1874 taxation law that increased the tax on the

monasteries to cover Church expenses.

Gregor Mendel died on January 6, 1884,

at the age of 61. He was laid to rest in the monastery’s burial plot and his

funeral was well attended. His work, however, was still largely unknown.

It was not until decades later, when Mendel’s research

informed the work of several noted geneticists, botanists and biologists

conducting research on heredity, that its significance was more fully

appreciated, and his studies began to be referred to as Mendel’s Laws. Hugo de

Vries, Carl Correns and Erich von Tschermak-Seysenegg each independently

duplicated Mendel's experiments and results in 1900, finding out after the

fact, allegedly, that both the data and the general theory had been published

in 1866 by Mendel. Questions arose about the validity of the claims that the

trio of botanists were not aware of Mendel's previous results, but they soon

did credit Mendel with priority. Even then, however, his work was often

marginalized by Darwinians, who claimed that his findings were irrelevant to a

theory of evolution. As genetic theory continued to develop, the relevance of

Mendel’s work fell in and out of favor, but his research and theories are

considered fundamental to any understanding of the field, and he is thus

considered the "father of modern genetics."

e) Referencias

bibliográficas

d) Preguntas relacionadas con las

ideas anteriores

¿En qué consistieron los experimentos de Mendel?

¿En qué consistieron los experimentos de Mendel?

Los

experimentos de Mendel sobre la herencia se realizaron con guisantes. Mendel

eligió está planta porque se reproduce con rapidez, permitiendo obtener varias

generaciones en un poco tiempo. Además, tiene rasgos que solo admiten dos

formas (los guisantes son lisos o rugosos, verdes o amarillos…) y son capaces

tanto de auto-polinizarse como de fertilizarse de forma cruzada.

En

sus experimentos, Mendel estudió siete características de la planta de

guisante: color de la semilla, forma de la semilla, posición de la flor, color

de la flor, forma de la vaina, color de la vaina y longitud del tallo.

Por

ejemplo, en una de sus pruebas Mendel cruzó dos variedades de guisantes: una

con flores purpuras y otra con flores blancas.

Esta era la generación P o parental, y su descendencia fue la F1 (primera

generación filial). La generación F1 luego se reprodujo por autopolinización,

Dando lugar a la generación F2.

El

resultado de la prueba fue bastante clarificador. Si en la generación parental

había el mismo número de guisantes con flores blancas que con flores purpuras,

en la F1 solo aparecieron flores purpura. Sin embargo en la generación F2

reaparecieron los guisantes con flores blancas, que representaron

aproximadamente ¼ de la descendencia.

¿Qué

concluyó Mendel con sus experimentos?

A

la vista de los resultados Mendel dedujo que el color purpura en la flor del

guisante era un rasgo dominante (A) y la flor blanca un rasgo recesivo (a).

Mendel observó el mismo patrón de herencia en otros seis personajes, cada uno

representado por dos rasgos diferentes. A partir de ahí llegó a las siguientes

conclusiones:

● Los

organismos tienen factores discretos que determinan sus características (estos

"factores" ahora se reconocen como genes)

●

Además,

los organismos poseen dos versiones de cada factor (estas 'versiones' ahora se

conocen como alelos)

● Cada

gameto contiene solo una versión de cada factor (ahora se sabe que las células

sexuales son haploides, es decir, solo tienen n cromosomas y no 2n, como el

resto de células del organismo)

●

Los

padres contribuyen igualmente a la herencia de la descendencia como resultado

de la fusión entre el óvulo y los espermatozoides seleccionados al azar.

●

Para

cada factor, una versión es dominante sobre otra y se expresará completamente

si está presente.

Later Life and Legacy

In 1868, Mendel was elected abbot of the

school where he had been teaching for the previous 14 years, and both his

resulting administrative duties and his gradually failing eyesight kept him

from continuing any extensive scientific work. He traveled little during this

time, and was further isolated from his contemporaries as the result of his

public opposition to an 1874 taxation law that increased the tax on the

monasteries to cover Church expenses.

Gregor Mendel died on January 6, 1884,

at the age of 61. He was laid to rest in the monastery’s burial plot and his

funeral was well attended. His work, however, was still largely unknown.

It was not until decades later, when Mendel’s research

informed the work of several noted geneticists, botanists and biologists

conducting research on heredity, that its significance was more fully

appreciated, and his studies began to be referred to as Mendel’s Laws. Hugo de

Vries, Carl Correns and Erich von Tschermak-Seysenegg each independently

duplicated Mendel's experiments and results in 1900, finding out after the

fact, allegedly, that both the data and the general theory had been published

in 1866 by Mendel. Questions arose about the validity of the claims that the

trio of botanists were not aware of Mendel's previous results, but they soon

did credit Mendel with priority. Even then, however, his work was often

marginalized by Darwinians, who claimed that his findings were irrelevant to a

theory of evolution. As genetic theory continued to develop, the relevance of

Mendel’s work fell in and out of favor, but his research and theories are

considered fundamental to any understanding of the field, and he is thus

considered the "father of modern genetics."

e) Referencias

bibliográficas

Comentarios

Publicar un comentario